The fossilers of South Cambridgeshire

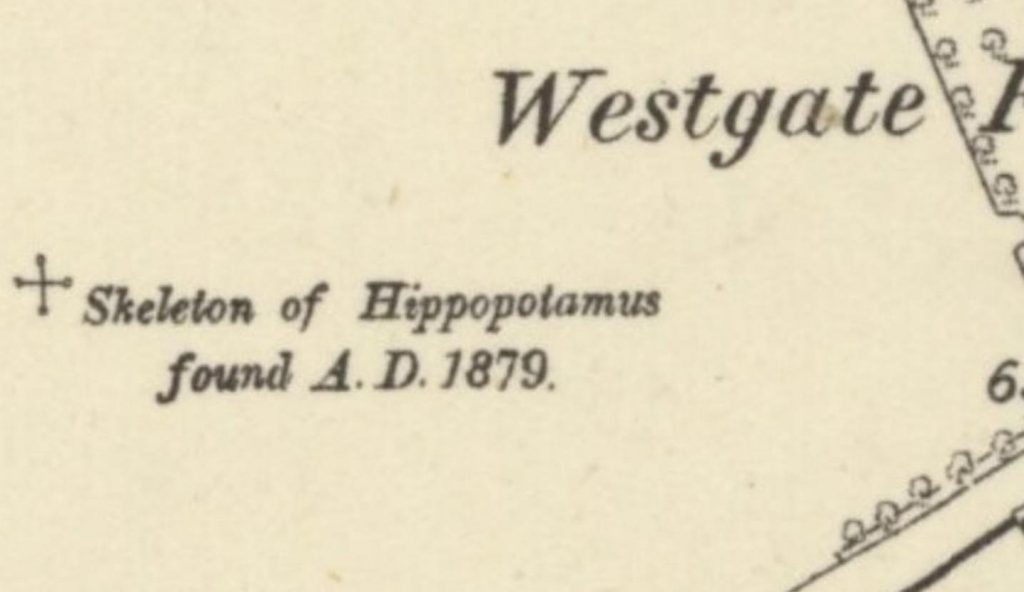

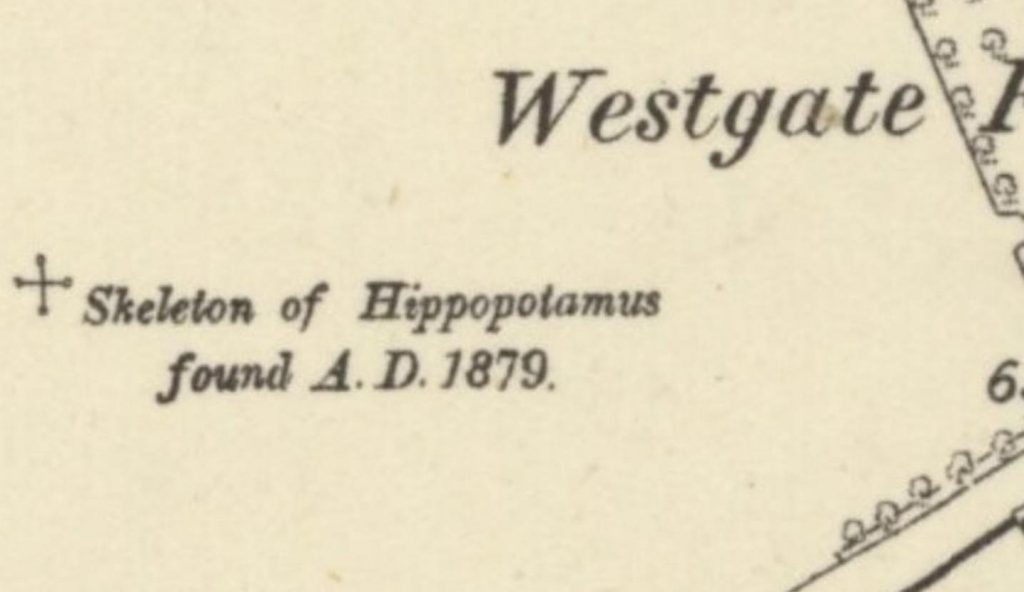

In July 1876, Edward Connybeare, the vicar of Barrington scribbled in his diary, ‘Grand specimen of a hippo was dug up in Roads’ field’. At nearby Harlton, Revd. Osmond Fisher, was equally thrilled to hear that more ‘large bones were being met with in a “coprolite-pit” at Barrington’. Fisher and the naturalist, collector and antiquarian Arthur Foster Griffith could not contain their excitement and rushed off to take a look. The pit was about 22 feet deep (the height of a two storey house) and the remains had already been removed, meaning the diggers – who were paid a piece-rate – could continue their work and their wage-packets would not suffer. It was not just hippos. There were also remnants of elephants, bison and hyena. As the pits were extended over the next 40 years, more and more bones from many different hippos kept being found. Eventually the Sedgwick Museum had enough bones from the various individuals to construct a complete skeleton. By fixing them all to a specially-made metal armature they created their own Frankenstein’s monster: a composite hippopotamus.[1]

It was not just animal bones, either. Much to Griffith’s dismay the coprolite-diggings in Barrington destroyed much of a large Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Hooper’s Field. Although he managed to save some of the artefacts for the Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology, many others were smuggled away and sold off by the dealers in antiquities at Cambridge. The past would clearly not get in the way of profit. It was a story that was repeated again and again from Coldham’s Common to Litlington, from Wendy to Burwell.[2]

But old bones and grave goods were not what the diggers were looking for, so exactly what was the coprolite they were so eager to find?

A burgeoning UK population needed increasing amounts of food and food production, in turn, required increasing amounts of fertiliser. Money was to be made from muck but not enough muck could be had. However, the strange greeny-black lumps of rock being slung out of the brick pits at Cambridge as waste provided a neat solution. Coprolite is now known to be made up of all sorts of fossilised remains (including those of marine life such as ammonites) but at the time was thought solely to be fossilised dinosaur poo. Over millions of years these remains had transformed into phosphate-rich nodules which could be found most abundantly in a geological formation known as the Cambridge Greensand. It did not take long for an enterprising farmer to realise that if he ground down coprolites and treated them with sulphuric acid, they transformed into a highly effective, and highly profitable, fertiliser.

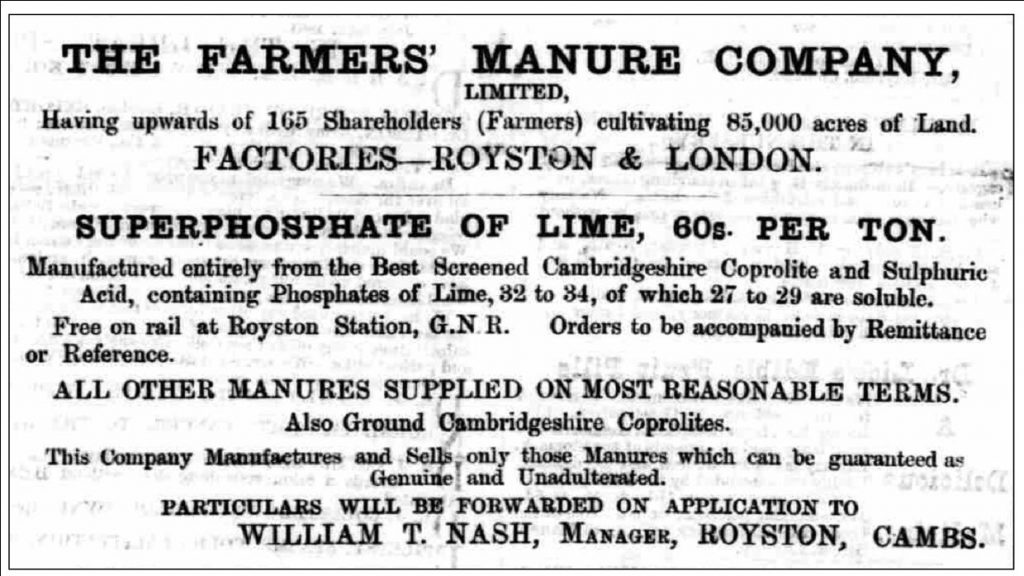

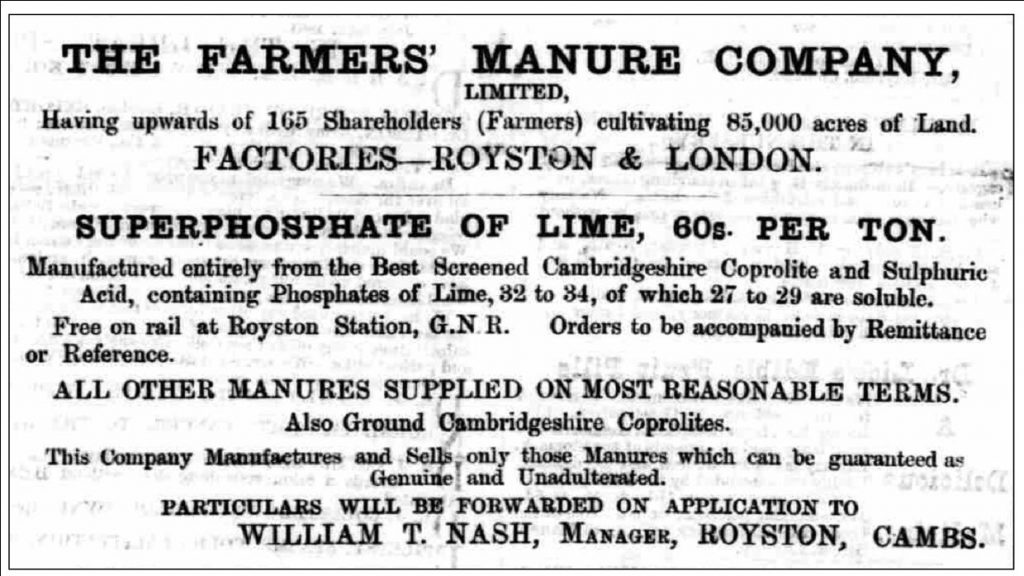

This seam of fossils sloped upwards, coming closest to the surface in a line north of Kneesworth. Soon open-cast diggings started springing up all along the narrow band of land in Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire and South Cambridgeshire where the Greensand was closest to the surface. On average the seam was about 30 cm thick and at its widest only 11 km wide. In villages such as Odsey, Bassingbourn and Shepreth, which had easy access to a railway, companies began processing the raw material and selling the fertiliser further afield. In Royston the Farmers Manure Company thrived (using Coprolites brought in by land-train) and at Duxford there was the Cambridge Manure Company.

This seam of fossils sloped upwards, coming closest to the surface in a line north of Kneesworth. Soon open-cast diggings started springing up all along the narrow band of land in Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire and South Cambridgeshire where the Greensand was closest to the surface. On average the seam was about 30 cm thick and at its widest only 11 km wide. In villages such as Odsey, Bassingbourn and Shepreth, which had easy access to a railway, companies began processing the raw material and selling the fertiliser further afield. In Royston the Farmers Manure Company thrived (using Coprolites brought in by land-train) and at Duxford there was the Cambridge Manure Company.

Agricultural labourers who changed trades and started to work for the coprolite contractors found their wages first doubling and then trebling. As a local folk-song from the time shows, previously struggling farm-workers now felt free to thumb their noses at their ex-employers.

Come listen you farmers to what I do say,

We Coprolite diggers now can have fair play…

With our spade and our pickaxe we’ve no work to seek.

We won’t work for farmers for ten bob a week.[3]

As people flooded into the area to work in the diggings, for the next thirty years the industry reversed a decline in village populations. At Shillington alone, 170 men and boys were soon working coprolites and, at the height of production in 1876, the wider-diggings produced 258,150 tons of artificial fertiliser in a single year. The local economy of Royston and the villages to the north benefitted hugely from this economic boom: land-owners made money selling licences to extract the coprolites and rising wages meant that workers now had money in their pockets to spend. In Barrington, the vicar’s ‘Coprolite Fund’ helped pay for repairs to All Saints and, in his History of Cambridgeshire, Reverend Connybeare reports, ‘This golden period has left an abiding mark upon the district in the restoration of almost every one of the ancient parish churches.’ [4]

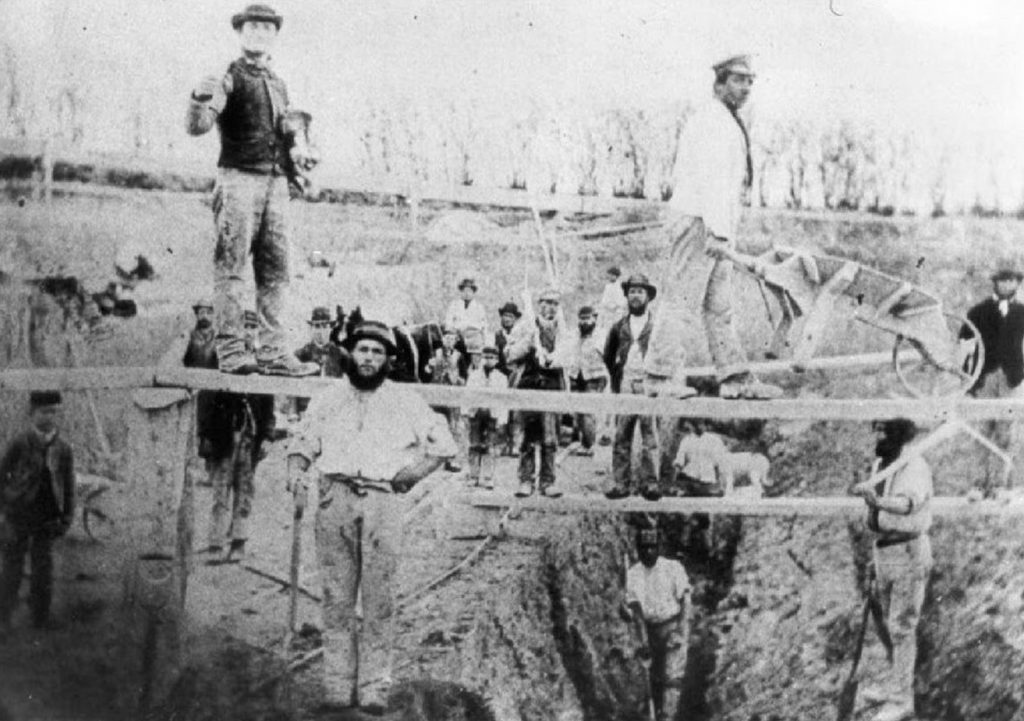

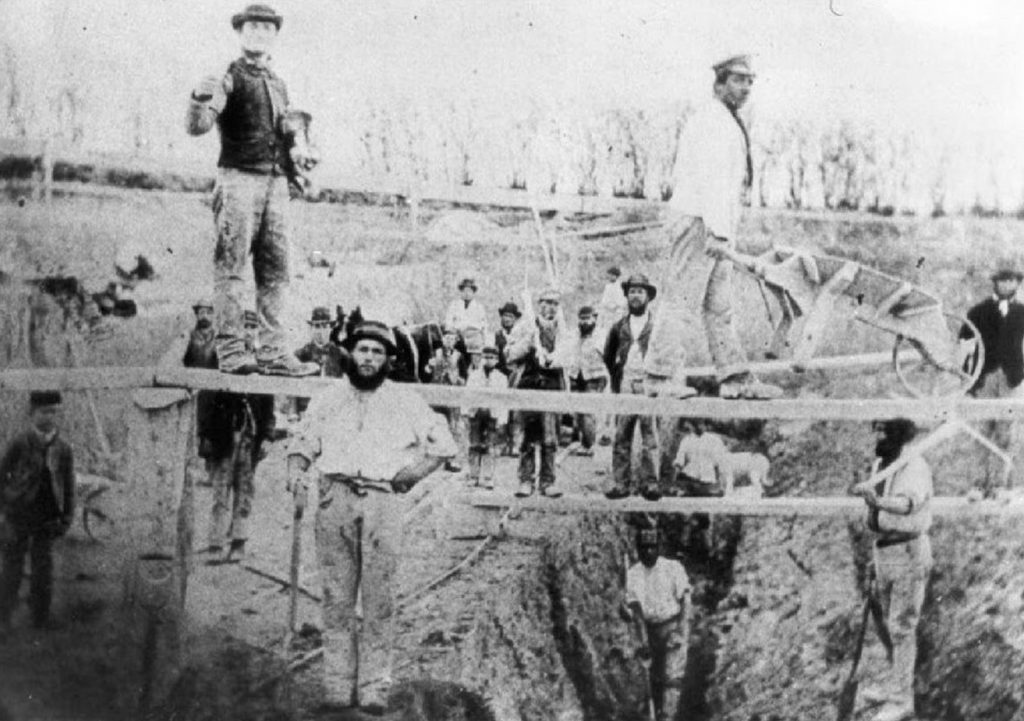

At the diggings, the money was hard-earned. The men first had to hand-dig a trench between 2 and 3 metres wide. The topsoil was wheel-barrowed away and carefully piled up, ready to be put back later. Then large quantities of subsoil had to be barrowed up to the top of the trench and ridged up there. Once they had reached the seam (which was sometimes more than 6 m below the surface), the diggers would dig into the side of the trench and undermine a slice of ground to the depth of 30 to 45 cm. In the best managed quarries watchmen were stationed above to give warning in case the ground should begin to crack and split away. If all went according to plan, the diggers would climb out of the trench before the ground was levered into the pit from above with crow bars. This left more of the coprolite seam exposed, ready to be shovelled into wheelbarrows and taken to the wash mills. It also conveniently back-filled the trench and revealed a new earth face ready to be undermined. In this way a whole field could be worked over. As the men were paid according to the amount they dug out, there was always pressure to work fast and the temptation to cut corners meant watchmen were often absent from their posts. Fatalities were common, the men drank hard and, when drunk, were given to riotous behaviour. It was claimed that more than half of them carried guns – and occasionally used them – and the local prostitutes were eager to service their hastily thrown up lodgings. Many God-fearing villagers were alarmed at this turn of events and one (Samuel Hopkins, a Bassingbourn grocer and Deacon of the Congregational Church) went as far as describing the diggers as ‘the refuse of society…extravagant, intemperate, licentious, depraved and atheistival.'[5]

Fatalities were common, the men drank hard and, when drunk, were given to riotous behaviour. It was claimed that more than half of them carried guns – and occasionally used them – and the local prostitutes were eager to service their hastily thrown up lodgings. Many God-fearing villagers were alarmed at this turn of events and one (Samuel Hopkins, a Bassingbourn grocer and Deacon of the Congregational Church) went as far as describing the diggers as ‘the refuse of society…extravagant, intemperate, licentious, depraved and atheistival.'[5]

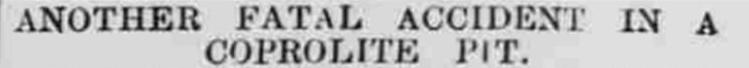

If these men lived fast, they died fast too. Mishaps were commonplace. Most of the casualties were buried alive by unexpected falls of earth or accidentally toppled from precariously balanced planks while pushing full barrows, others drowned in flooded pits and at least one man fell into a washing mill. Nobody knows how many people died in the coprolite pits but, after a search of the local newspapers, here are just some of their names:

1858: Arthur Wellington Reach (aged 6)

1863: John Rayner (age unknown), William Lander (age unknown)

1864: James Dawson (age unknown)

1865: James Mann (age unknown), William Wilson (age unknown), James Rayner (aged 23)

1866: James Barton (aged 21)

1867: Richard Barlow (aged 11), John Swann (aged 60), James Day (aged 25)

1868: William Starbuck (aged 9)

1869: Robert Napsey (aged 19), Thomas Lovell (aged 36), James Fortune (age unknown), Moses Waller (age unknown)

1870: William Crane (‘a young man’), George Aspen (aged 26)

1871: George Hills (aged 61), William Clarke (age unknown), John Dockrey (aged 18)

1874: William Hines (aged 25)

1875: Edward Wilkin (aged 23)

1876: George Wright (age unknown)

1877: Henry Ginn (aged 37), a boy named Parker (age unknown)

1878: Wheeler Ambrose (aged 46)

1879: George Fuller (aged 27)

1883: William Wright (age unknown)

1887: Harradine Sell (aged 47)

If the dead man was married, the fellow-labourers would have a whip-round for his widow. Inquests invariably recorded verdicts of ‘accidental death’ and no contractor was obliged by law to pay any compensation. The Cambridge Chronicle reported that some (like Mr Cooper at Barrington), however, did display ‘kindness’ and at least paid for the man’s funeral. [6]

Non-fatal accidents and ‘lucky escapes’ were rarely reported in the papers. At the time, the Cambridge Chronicle noted that ‘nearly every week accidents happen and bones are broken, which few of the public are aware of.’ Four years later, in 1875, the Governors of Addenbrooke’s Hospital took the highly unusual step of writing to the Home Secretary to draw his attention to ‘the great number of accidents that occur in the working of the coprolite pits’. In his reply, the government minister displayed a complete lack of understanding: digging the trenches was no more dangerous than digging a railway cutting and ‘the accidents occurred from the extreme carelessness of the men’.[7]

Ironically, twenty years later when regulation did eventually come (in the form of the 1894 Quarries Act), it rang the death knell for an industry that was already on its last legs. The industry had collapsed in the early 1880s when poor harvests and the opening up of the home market to cheap imports of meat and grain from the Americas had crippled farmers. By 1897 Connybeare was lamenting, ‘The coprolites have become exhausted, agriculture has failed, wages have sunk to ten shillings a week…Many labourers are unemployed, and many more have left the County, the population of which (in the rural districts is rapidly sinking)…Cambridgeshire has become for the first time one of the poorest counties in England.'[8]

Although there were a couple of later minor surges in coprolite diggings (most notably during the First World War when the coprolites were used to produce explosives), they were never anything like the boom of the 1870s and, although it diversified and changed its name, the Farmers Fertiliser Company of Royston ceased trading around the 1970s.

From the air, the ghosts of the many workings can still be spotted in the fields but there is no memorial to those who lost their lives.

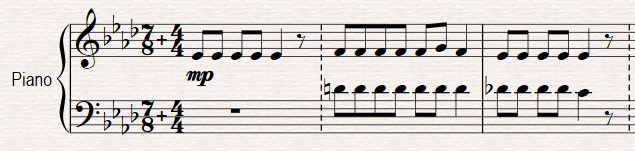

(The history of the coprolite workers forms the basis of one of the Cracked Voices).

If you would like to discover more about the Coprolite Rush, I highly recommend the series of booklets based on the various individual diggings written by Bernard O’Connor. See: http://bernardoconnor.org.uk/coprolites.html .

[1] Revd. Edward Conybeare’s Diary, quoted in Barrington Fossil Diggings, Bernard O’Connor (2011), p.29; The Quarterly journal of the Geological Society of London, vol. 35 (1879) p.670(diagram: page 671)

[2] Sussex, Archaeological Collections Relating to the History and Antiquities of the County, Vol.55 (Sussex Archaeological Society, 1912), p.63-67

[3] The Horningsea Fossil Digging, Bernard O’Connor (2011), p.37-38 (original in the possession of the Sclaters, Abington Piggotts)

[4] http://www.cafg.net/docs/articles/Wimpole%20coprolites.pdf; History of Cambridgeshire, Revd. Edward Connybeare (1897), p.259

[5] Original manuscript in the possession of Bassingbourn Congregational Church, pp.210ff. Quoted in Coton Fossil Diggings, Bernard O’Connor (2011) p.65

[6] Cambridge Chronicle and Journal , Saturday 15 October 1864

[7] Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, 13 May 1871; Cambridge Independent Press, 4 September 1875

[8]’The Origins and Development of the British Coprolite Industry’, Bernard O’Connor in Mining History: The Bulletin of the Peak District Mines Historical Society, Volume 14, No. 5, Summer 2001, p.46-57. Available online at: http://archive.pdmhs.com/PDFs/ScannedBulletinArticles/Bulletin%2014-5%20-%20The%20Origins%20and%20Development%20of%20the%20British%20.pdf ; History of Cambridgeshire, Revd. Edward Connybeare (1897), p.268-269

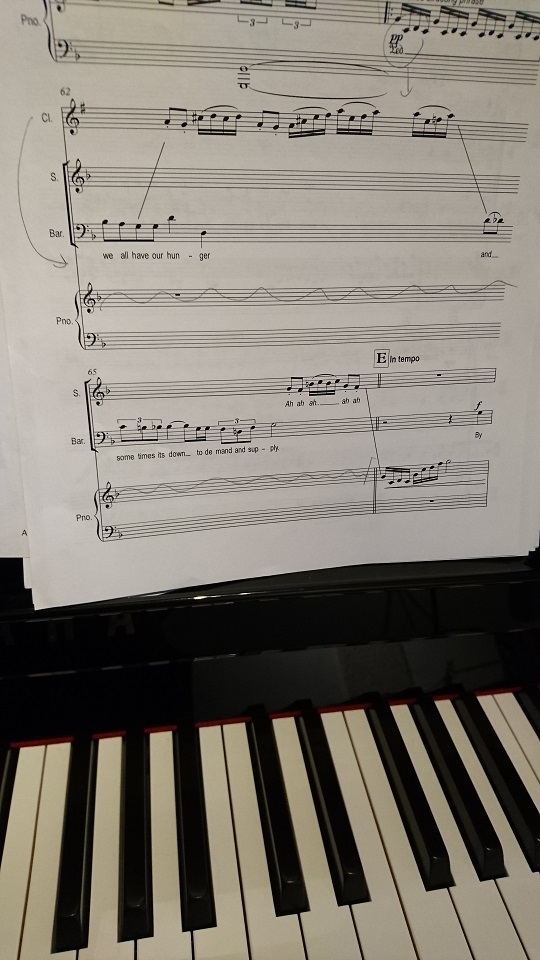

Thank you to everyone who came to our premiere at Cambridge’s Anglia Ruskin University. It was a joy to be able to share Cracked Voices with you. For us it was a moving experience hearing Miles Horner, Donna Lennard, Sue Pettitt and Ralph Woodward taking the songs and making them their own (all photos are from our pre-performance rehearsal).

Thank you to everyone who came to our premiere at Cambridge’s Anglia Ruskin University. It was a joy to be able to share Cracked Voices with you. For us it was a moving experience hearing Miles Horner, Donna Lennard, Sue Pettitt and Ralph Woodward taking the songs and making them their own (all photos are from our pre-performance rehearsal).

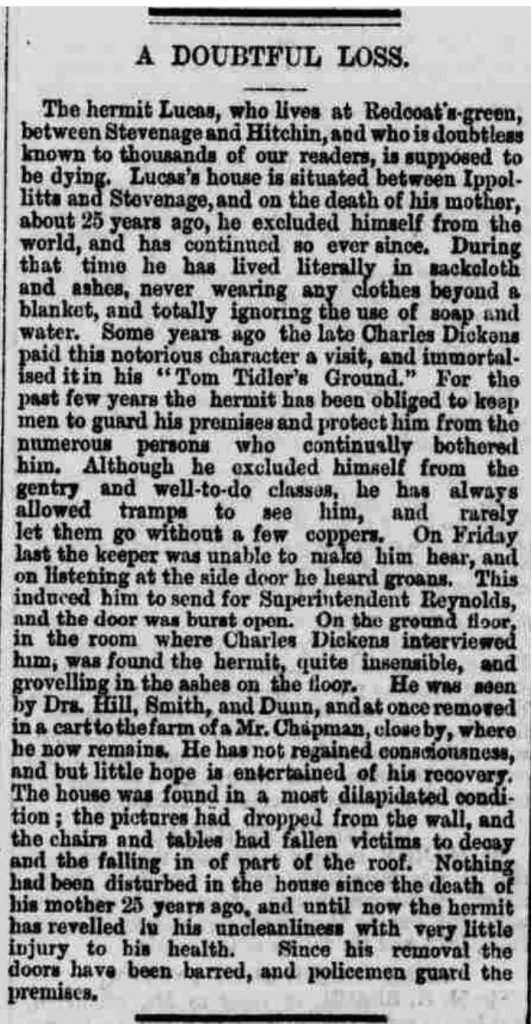

That December Dickens published a damning account of his visit to Redcoats Green in the Christmas edition of All Year Round. ‘

That December Dickens published a damning account of his visit to Redcoats Green in the Christmas edition of All Year Round. ‘

Doing History in Public is a collaborative blog written and edited by graduate historians (mainly at the University of Cambridge). Graham was delighted to be invited to share information about the challenges behind researching and writing Cracked Voices.

Doing History in Public is a collaborative blog written and edited by graduate historians (mainly at the University of Cambridge). Graham was delighted to be invited to share information about the challenges behind researching and writing Cracked Voices.

This seam of fossils sloped upwards, coming closest to the surface in a line north of Kneesworth. Soon open-cast diggings started springing up all along the narrow band of land in Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire and South Cambridgeshire where the Greensand was closest to the surface. On average the seam was about 30 cm thick and at its widest only 11 km wide. In villages such as Odsey, Bassingbourn and Shepreth, which had easy access to a railway, companies began processing the raw material and selling the fertiliser further afield. In Royston the Farmers Manure Company thrived (using Coprolites brought in by land-train) and at Duxford there was the Cambridge Manure Company.

This seam of fossils sloped upwards, coming closest to the surface in a line north of Kneesworth. Soon open-cast diggings started springing up all along the narrow band of land in Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire and South Cambridgeshire where the Greensand was closest to the surface. On average the seam was about 30 cm thick and at its widest only 11 km wide. In villages such as Odsey, Bassingbourn and Shepreth, which had easy access to a railway, companies began processing the raw material and selling the fertiliser further afield. In Royston the Farmers Manure Company thrived (using Coprolites brought in by land-train) and at Duxford there was the Cambridge Manure Company.

Fatalities were common, the men drank hard and, when drunk, were given to riotous behaviour. It was claimed that more than half of them carried guns – and occasionally used them – and the local prostitutes were eager to service their hastily thrown up lodgings. Many God-fearing villagers were alarmed at this turn of events and one (Samuel Hopkins, a Bassingbourn grocer and Deacon of the Congregational Church) went as far as describing the diggers as ‘the refuse of society…extravagant, intemperate, licentious, depraved and atheistival.'[5]

Fatalities were common, the men drank hard and, when drunk, were given to riotous behaviour. It was claimed that more than half of them carried guns – and occasionally used them – and the local prostitutes were eager to service their hastily thrown up lodgings. Many God-fearing villagers were alarmed at this turn of events and one (Samuel Hopkins, a Bassingbourn grocer and Deacon of the Congregational Church) went as far as describing the diggers as ‘the refuse of society…extravagant, intemperate, licentious, depraved and atheistival.'[5]