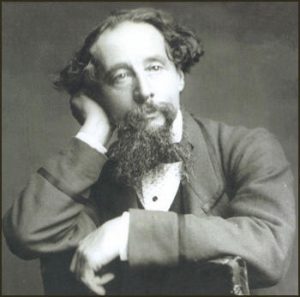

The megastar had arrived. With his distinctively high forehead, curling hair and aggressively jutting beard, no-one could mistake the great Charles Dickens as he stepped down into the quiet country lane at Redcoats Green near Hitchin. But, alas, apart from a watchman, there was no-one there to witness his arrival.

That year, gossip of his extraordinary extra-marital arrangements was still helping news-vendors’ earn their crust. Having separated from his wife, Dickens was rumoured to be sleeping with his sister-in-law and housekeeper, Georgiana Hogarth. Along with his eldest daughter, Georgiana had accompanied him to Knebworth House where Dickens was weekending with Edward Bulwer-Lytton.

That year, gossip of his extraordinary extra-marital arrangements was still helping news-vendors’ earn their crust. Having separated from his wife, Dickens was rumoured to be sleeping with his sister-in-law and housekeeper, Georgiana Hogarth. Along with his eldest daughter, Georgiana had accompanied him to Knebworth House where Dickens was weekending with Edward Bulwer-Lytton.

The final draft of Great Expectations was complete and he was eager to share it with Lytton, a highly-respected writer in his own right. In this version, the reclusive Miss Havisham would die horrifically in a fire – killed by her own wedding dress – and Estelle would marry, leaving poor Pip destitute of hope. The great writer was uneasy. Did the ending work? At Knebworth, Bulwer-Lytton read over his friend’s work and suggested it was a little too down-beat. Dickens later wrote, ‘I have resumed the wheel, and taken another turn at it…I think it is for the better.’ The finished piece did not placate Dickens’ critics though. When Great Expectations was finally published in book form a few weeks later it received mixed reviews. The Morning Post claimed he had ‘betrayed his public’ and called its plot an offence against all laws of probability.[1]

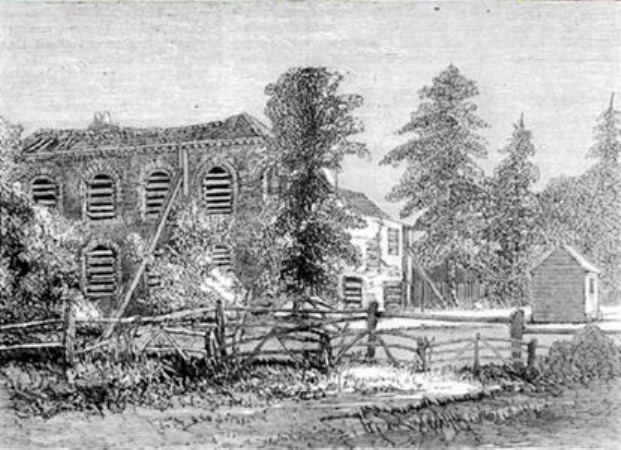

Redcoats Green was to be a diverting day excursion from Knebworth. But as Dickens’ carriage halted in the quiet country lane, the only person who stirred was an Irishman, watching from an old shepherd’s hut whose wheels showed signs of not having moved for years. The house he was guarding had once been the modest country dwelling of a gentleman. Now it was collapsing in on itself. Its gardens were tangled in weeds and the grounds were secured by a barricade of sheep-hurdles, its broken windows barred with roughly-cut timbers. In the coach-house, the painted family crest was fading on a once-grand carriage, now worm-eaten and covered with thick cobwebs. Given the popularity of everything Gothic, other curious tourists and roving down-and-outs would soon likely-as-not come traipsing down the lane either on foot or horseback. The decaying house was a disturbing sight for Dickens who remained deeply troubled by memories of the degradation of the debtors’ prison. Forced to abandon school at 12, he had managed to feed the family by working ten hours a day, pasting labels on pots of boot blacking. It was this savage experience – the life and death struggle to make ends meet – that fuelled his social conscience and found expression through his novels. Later, he was to write ‘my whole nature was so penetrated with grief and humiliation that even now, famous and caressed and happy, I often forget in my dreams…that I am a man; and wander desolately back to that time of my life.’ What greeted him at Redcoats Green challenged every lesson he had learned from his own miserable childhood. Staring through a barred basement window into a filthy kitchen, he was truly disgusted.[2]

The decaying house was a disturbing sight for Dickens who remained deeply troubled by memories of the degradation of the debtors’ prison. Forced to abandon school at 12, he had managed to feed the family by working ten hours a day, pasting labels on pots of boot blacking. It was this savage experience – the life and death struggle to make ends meet – that fuelled his social conscience and found expression through his novels. Later, he was to write ‘my whole nature was so penetrated with grief and humiliation that even now, famous and caressed and happy, I often forget in my dreams…that I am a man; and wander desolately back to that time of my life.’ What greeted him at Redcoats Green challenged every lesson he had learned from his own miserable childhood. Staring through a barred basement window into a filthy kitchen, he was truly disgusted.[2]

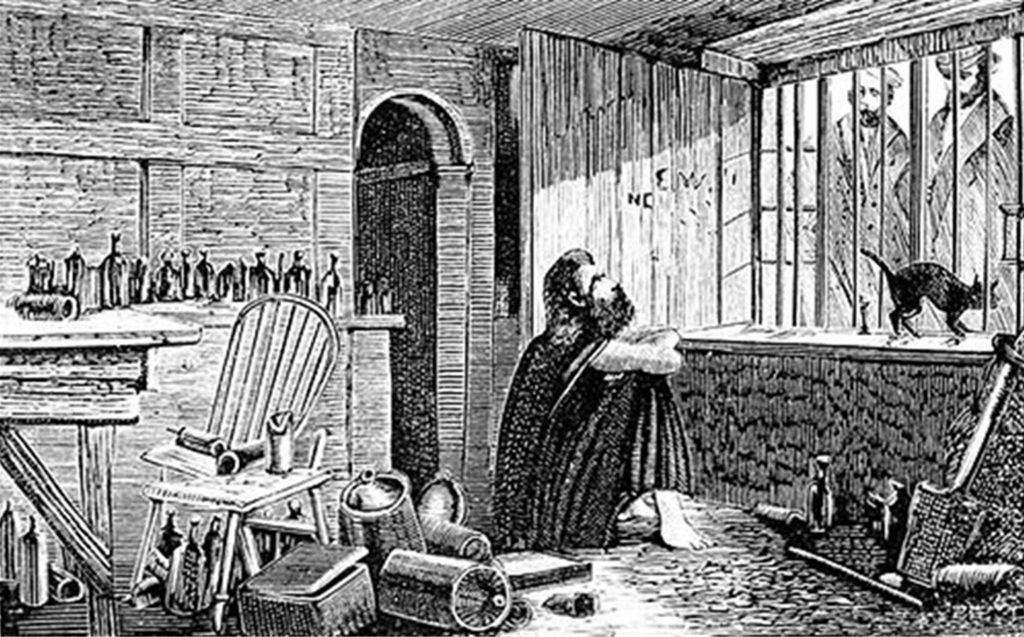

On a pile of soot, surrounded by scraps of stale bread and wearing nothing but a filthy blanket sat a rich man – a man who had chosen to throw his wealth away and waste every hour of his blessed life. A celebrity – famous for doing nothing – a ‘slothful, unsavoury, nasty reversal of the laws of human nature’ living a ‘highly absurd and highly indecent life’ (Dickens’ words, not mine).

The object of Dickens’ derision was James Lucas – an articulate, intelligent and contrary man who quizzed his visitors unmercifully and had a wide knowledge of what was happening in the world. A man who did not suffer others’ puffed-up egos lightly.

The James Lucas whom Dickens could not see was ill – a paranoid schizophrenic, convinced that his brother George had murdered his mother and was plotting to kill him. A man who shut himself away for his own safety.

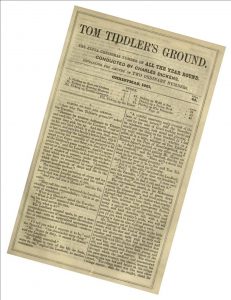

That December Dickens published a damning account of his visit to Redcoats Green in the Christmas edition of All Year Round. ‘Tom Tiddler’s Ground’ (named after a children’s game of ‘dare’ where children had to run into forbidden territory and gather up pretend coins before scary Tom could catch them), portrayed Lucas as nothing more than an arrogant waster. That piece had reporters flocking to interview ‘the hermit’ and one, Edward Copping from London Society, was left aghast at his intellect. ‘He overturns my opinions with ruthless energy, he kicks them when they are down, he pummels them with his two fists; and in a short time they are so bruised and disfigured as to be scarcely recognisable’. Perhaps this ability to demolish preconceptions is what had so offended Dickens. Whatever the great writer’s intentions, ‘Tom Tiddler’s Ground‘ cemented Redcoats Green as a go-to destination for the daring Victorian day-tripper and the Great Northern Railway was soon advertising weekend excursions ‘to see the Hermit of Hertfordshire’.[3]

That December Dickens published a damning account of his visit to Redcoats Green in the Christmas edition of All Year Round. ‘Tom Tiddler’s Ground’ (named after a children’s game of ‘dare’ where children had to run into forbidden territory and gather up pretend coins before scary Tom could catch them), portrayed Lucas as nothing more than an arrogant waster. That piece had reporters flocking to interview ‘the hermit’ and one, Edward Copping from London Society, was left aghast at his intellect. ‘He overturns my opinions with ruthless energy, he kicks them when they are down, he pummels them with his two fists; and in a short time they are so bruised and disfigured as to be scarcely recognisable’. Perhaps this ability to demolish preconceptions is what had so offended Dickens. Whatever the great writer’s intentions, ‘Tom Tiddler’s Ground‘ cemented Redcoats Green as a go-to destination for the daring Victorian day-tripper and the Great Northern Railway was soon advertising weekend excursions ‘to see the Hermit of Hertfordshire’.[3]

For over a decade the ‘hermit’ continued to hold court until, on a spring morning in 1874, his watchman found him groaning and gasping for breath, having suffered a stroke in the night. A doctor had James placed in a horse drawn cart (so very different from the elegant family carriage) and taken to a nearby farmhouse. He died there two days later. The Dundee Courier ran the news under the headline ‘The death of one of Dickens’ characters’ and other papers followed The Times lead and echoed popular sentiment, calling it ‘A doubtful loss’.[4]

Notes

[1] The Selected Letters of Charles Dickens (Oxford, 2012) p.360; The Letters of Charles Dickens, Volume 2 (London, 1880) p.142-143; Morning Post, Wednesday 31 July 1861; Herts Guardian, Agricultural Journal, and General Advertiser – Saturday 10 August 1861, Tuesday 13 August 1861

[2] The life and times of Charles Dickens, Peter Ackroyd (Califiornia, 2003), p.11

[3] ‘Mr Mopes, the Hermit’, London Society, Volume 1 (March 1862) p.303-313 ( )

[4] Hertfordshire Express and General Advertiser – Saturday 26 January 1867; Â Herts Advertiser – Saturday 02 May 1874 (quoting the Telegraph); Dundee Courier – Monday 27 April 1874; Western Mail – Tuesday 21 April 1874 (echoing the Times), Western Times – Tuesday 28 April 1874

Published over thirty years ago, Richard Whitmore’s Mad Lucas remains the best biography of the Hertfordshire hermit.

The conversation between James Lucas and Dickens forms the basis for one of the songs of Cracked Voices, ‘A doubtful loss’.