Last week Graham and Jenni were on BBC Radio Cambridgeshire’s Lunchtime Live, talking to Thordis Fridriksson about Cracked Voices! Listen again (for the next 10 days) on iPlayer Radio.

Cracked voices, thingmebobs and whatchamacallits…

The fraught art of naming things

Naming things is fundamental to us. It’s how we define the world and ourselves.

Words are always dangerous and, as any playground bully knows, names are the most dangerous of all. They can scar us for life.

Ask any soon-to-be-parent who’s ever puzzled their way through a book of baby names. Just what do you choose? Is it John or Jon or even Juan? Isobel or Isabelle or Issy?

Names matter. They label us and stick much longer than post-its. They are full of magic.

In past times, many people believed in invisible beings such as fairies but using the name was extremely unlucky. Instead they were ‘the wee folk’, ‘the Gentry’ or ‘the Hidden Company’. More recently, JK Rowling hit the nail (or was it a tack, brad or pin?) squarely on the head with ‘He-who-must-not-be-named!’

Tolkien, the master of naming things, based Bree on the Buckinghamshire town of Brill. Now Brill is a lovely place, built on a hill with its own windmill. I visited it once and was treated to a slap up tea by the ladies at the Methodist Church there – but that’s a different story.

Brill on the Hill © Copyright Bill Nicholls and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

Brill’s first inhabitants (or at least the first who fixed its name) called it Breg, literally ‘hill’ in the local Celtic language. When the Anglo-Saxons invaded they asked a local what this large lump in the ground was called and were told Breg. Now in Anglo-Saxon a lump in the ground was a hyll, so naturally enough the newcomers now started calling the place Breg Hyll. Eventually this was shortened to Brill. Now, since most of us no longer speak Common Brittonic or Old English, naturally enough locals in the twenty-first century refer to the lump in the ground that the town is built on as Brill Hill. So over time the place has become Hill Hill Hill. Names are so difficult!

Names always carry hidden messages from the past. Have you ever wondered why we kill a cow (from the Old English cū) but eat beef (from the French boeuf). Could it have anything to do with the Norman Invasion? After 1066 it was the local Anglo-Saxons who slaughtered the animals but the rich French-speaking Normans who ate the meat. (No, this has nothing to do with Brexit!).

But what has all this got to do with Jenni, me or song cycles? Well, a Pinnock is a dialect name for a hedge sparrow – Palmer, the Anglo-Norman for a pilgrim: creatures whose habitats have over time been eroded by both carelessness and lack of care. But that’s not it!

What could we call a song cycle about people whose stories and names have been forgotten? People who lived on the edge and had fallen over it. There was only one choice really:

cracked

adjective

1. damaged and showing lines on the surface from having split without coming apart.

2. informal. crazy; insane.

voice

noun

1. the sound produced in a person’s larynx and uttered through the mouth, as speech or song.

2. a particular opinion or attitude expressed.

The art of the art song

Let’s start at the very beginning! Before I start posting about how I’m composing some of the Cracked Voices pieces, I thought I’d talk a bit about art songs and their history.

To put it bluntly, an art song is a poem set to music. Traditionally they are secular, and feature a pianist and a singer. Sometimes they feature more than one vocalist – in our case, we’re using both a soprano and a baritone. More unusually, we’ll also be augmenting the setup with one further instrument, which is uncommon but not unheard of! They’re designed to be performed in a more formal setting, such as concerts and recitals, which differentiates them from musical theatre songs, folk songs and popular songs. Grove rather amusingly defines them as “a short vocal piece of serious artistic purpose” which makes them sound all too serious, but their subject matter be absolutely anything, be it humour or discussing death!

A song cycle, then, is a collection of art songs linked together. The link could be a very vague thread, or they could be intrinsically tangled together. Obviously the subject matter will be the predominant link in Cracked Voices, but there are others that I’m sure we’ll discuss later.

Some people are more familiar with the term lieder than art songs – the term more specifically for German polyphonic art songs. Schubert is historically the king of lieder, having written over 600 in his lifetime. I was introduced to a vast array of art songs at university (predominantly lieder!) when accompanying some wonderful singers for various workshops and recitals, which is where my love of them began. Below is a recording of one I’ve acccompanied several times – Schubert’s famous Erlkönig, complete with animation (and one of the few recordings I’ve seen that credit the performers). This was recorded by Oxford Lieder as part of their Schubert Project.

Various composers have written art songs in a multitude of languages. If you’re interested in finding some others, The Art Song Project have recorded a whole range, including a lot by living composers (and the one of mine below!).

One constant worry for all writers of new music is how do we draw new audiences in? Some audiences would find new music scary, and may be daunted by an evening dominated by a newly commissioned lengthy symphony. In a song cycle, however, each song tends to be short and sweet – averaging around three minutes in length (shorter than your average pop song!). Each of ours will have characters and a story behind it too, which when coupled with Graham’s wonderful writing will make these art songs excellent for anyone to sink their teeth into, whether they’re a music academic or a newcomer to the concert scene (and anywhere in between!).

In time I hope to share a few snippets of the Cracked Voices songs – sneak previews before the 2018 premiere! To give you a bit of a taste in the meantime, here’s an art song of mine composed back in 2013 – Bells in the Rain, performed here by Hélène Lindqvist and Philipp Vogler of The Art Song Project.

Cracked Voices in the Royston Crow and on BBC Radio Cambridgeshire

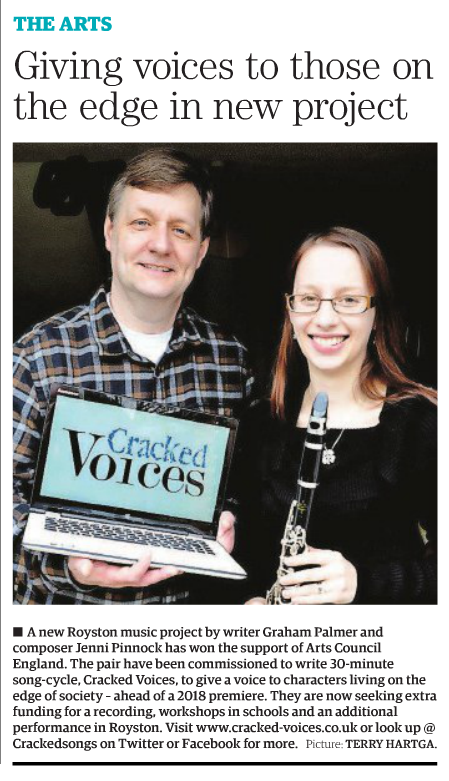

Thank you to the Royston Crow for covering our Cracked Voices project in this week’s edition!

Clipping of Cracked Voices from the Royston Crow

We’re also very excited to share that we’ll be on the local Arts&Ents section of BBC Radio Cambridgeshire’s Lunchtime Live on Monday 6th March, between 2pm and 3pm talking about the project.