Scales are a staple of musical life. If you learn a musical instrument, you end up playing them (sometimes seemingly endlessly!) and learning how they work is an important chunk of musical theory.

Not all scales are created equal. Western music relies on equal temperament, where the octave is divided into 12 equal parts, or semitones. However, our perception of the musical world as a whole is based on just intonation and the harmonic series. As a result, rather than all sounding the same, scales in equal temperament each have a different feeling. I once did a survey to try and find out composer’s favourite scales, but ultimately it depends on the piece in question. For example, I find E major a bit too ‘major’, but E flat major more rounded, with D flat major being a favourite. Minor wise, I’m not a huge fan of A minor, but E minor or C minor I do like, and D minor feels very traditionally ‘minor’.

As a result, finding the tonal centres and scales to use in a piece are a fundamental point for me. They have to work with the piece, its feeling, and with the performers in question too, as transposing to another key often feels rather wrong.

Major and minor scales are those focused on most in traditional music exams. Chromatic scales (using all 12 semitones in an octave, white and black notes) are practiced too, and some exams include pentatonic (five note- think Javanese gamelan!) and whole tone (dream sequence) scales too. For this piece I wanted something slightly more unusual than any of the above.

The blessing of the road-born child is a mother’s song to her child, born on the road. The tonality needed to be something not too major or minor, and with a bit of a twist. Instead of looking at the traditional majors and minors I headed to the modes – seven scales which all have different combinations of intervals, giving them distinct sounds (for more on modes, see here). Although I studied them extensively at university (we had to identify them by sound in pieces!) and I know they’re focused on in jazz exams, they’re a scale that’s less well known today outside of the jazz community – maybe due to their lack of inclusion in standard classical exams.

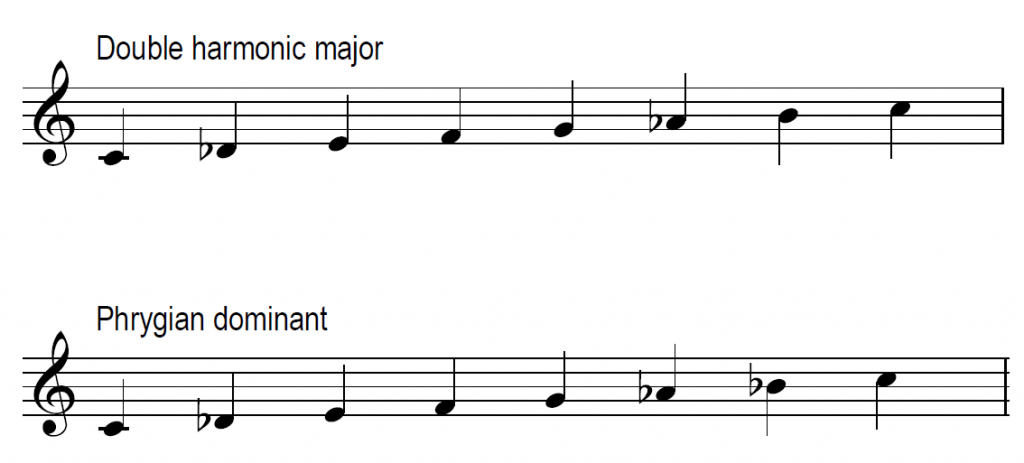

Playing with different modes, the instant solution was the phrygian mode. The minor second interval at the beginning means it’s not used as much as some of the other modes, but it felt just right for this. However, I wanted to have the major 7th at the top of the scale alongside the minor one. This left me with two scales to work with: The phrygian dominant, and the double harmonic major.

The next task was to find where they fit best on the piano, if at all. This involved playing around with them on the piano, sketching out some ideas and seeing what felt right. Graham and I had already discussed instrumentation for this piece and we knew we wanted to go with a clarinet and soprano duet, ignoring the piano completely. A bit of singing and improvising on both instruments playing with the scales cemented E being the tonic to begin with, rising to F towards the end.

It was a little later that I discovered the alternative names of the scales I’ve picked to centre the piece around. Both are often referred to as gypsy or gipsy scales – phrygian dominant the Spanish gypsy scale, and the double harmonic major scale as gypsy major. Clearly they were meant to be!