The cat, the witch and other myths…

Curiosity killed the cat.

If you believe some blogs, the cat was first killed at the turn of the 20th century. Wikipedia claims that the saying first appeared in print in 1873 but a brief search of the British Newspaper Archive reveals it was in common usage in Ireland well before that.

So what does that prove? Not a lot. Just that you shouldn’t take things you read at face value (not even this)…and that’s the most important thing any would-be researcher can learn.

A lot of what we take for granted about the past is – well – alternative facts. It’s not so much fake news as misremembered myths. Just as in the children’s game of Chinese Whispers, the history that gets passed on subtly alters with each retelling. By the time we finally hear the story it has little resemblance to the one that was first told but that doesn’t make it essentially untrue.

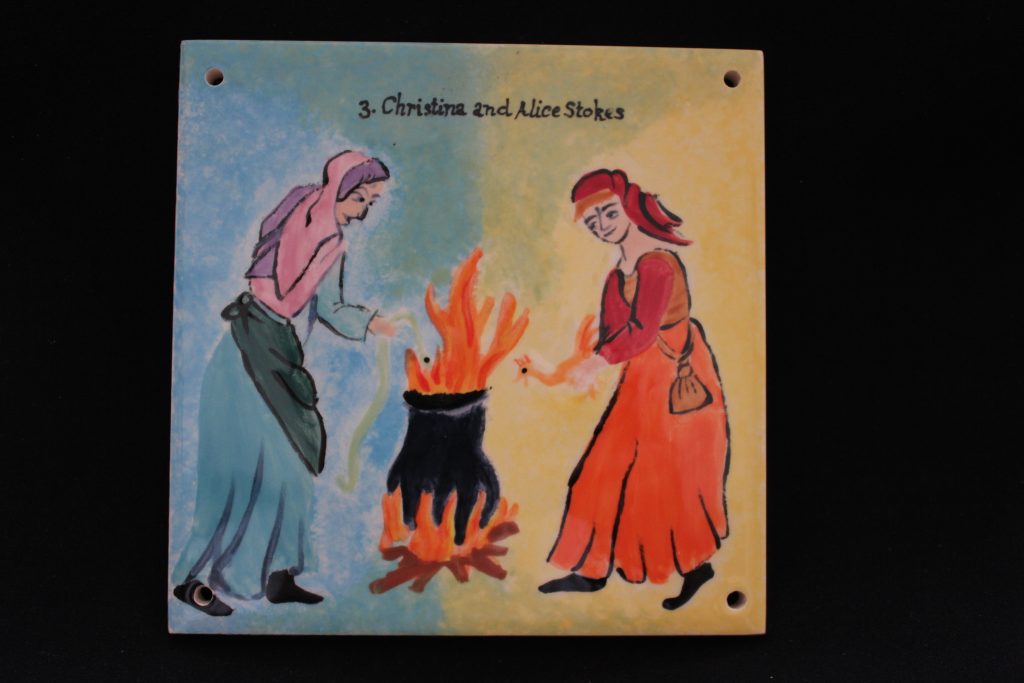

Take the Royston witches. As far as I know, they didn’t have a black cat, nor did they boil up animals in a large cauldron or fly through the air. Since I rediscovered them for Creative Royston in 2014, this however has become the dominant picture people have of them, largely due to an image created for an art trail at the time.

Royston witches

Let’s return to the whisper I first heard in 2014. I had not set out to search for witches. I was looking for something else entirely when I came across a reference to Royston in a book. That book (Witchcraft in England, 1558-1618) reprints part of a pamphlet from 1606 called The most cruell and bloody murther committed by an Inkeeper’s Wife… A copy of the original pamphlet is held at the British Library in Euston and anyone can access the original there (for anyone interested, it’s also transcribed here). Like so many other cheap chapbooks, it was not printed to provide an accurate report of recent happenings but rather to ensure they were sensationalised in a way that would confirm the readers’ prejudices, increase sales and make the publisher and street-sellers a fast buck.

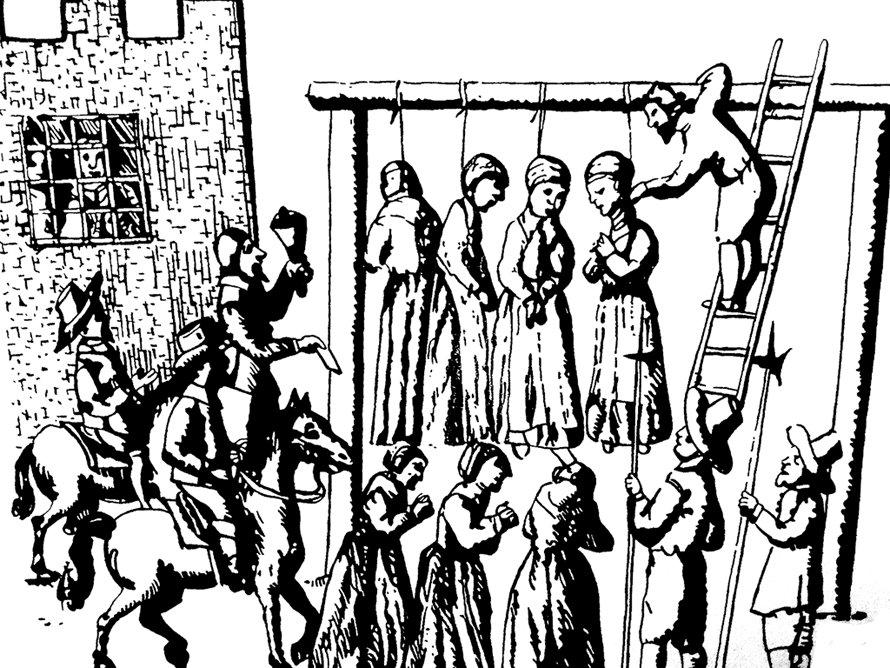

After dealing with the Hatfield murderers, the pamphlet goes on to tell another story – that of Joan Harrison and her daughter, two women from Royston who were executed for witchcraft that August. Or does it?

The chapbook is full of accusations and intriguing detail but gets the basic facts wrong. Its writer may not even have been in Hertford for the Assizes but possibly only heard the story second hand. If you trawl through the court records held at the National Archive in Kew you can go back to that first whisper. In the indictments for the Hertford Summer Sessions (NA, ASSI 35/48/2)* the Royston women are named as Alice Stokes and Christiana Stokes, not mother and daughter but both spinsters (possibly sisters). So how much else in the pamphlet is actually accurate? And why were Alice and Christina suddenly singled out in 1606?

King James of Scotland had come to the English throne only three years earlier. On his journey south he had stopped in Royston and taken note of the good hunting to be had on the extensive heathlands. This was a man who was fascinated with witchcraft, who had previously written a book on it called Daemonologie. This was the year of Shakespeare’s new play Macbeth – where witches haunt the heath – and, apart from hunting, James himself also participated in a number of witch-trials. The king had recently established a bachelor pad in Royston, so what could be more politic for the locals than to furnish him with two women to hang?

King James of Scotland had come to the English throne only three years earlier. On his journey south he had stopped in Royston and taken note of the good hunting to be had on the extensive heathlands. This was a man who was fascinated with witchcraft, who had previously written a book on it called Daemonologie. This was the year of Shakespeare’s new play Macbeth – where witches haunt the heath – and, apart from hunting, James himself also participated in a number of witch-trials. The king had recently established a bachelor pad in Royston, so what could be more politic for the locals than to furnish him with two women to hang?

Of course, this is all pure speculation as no contemporary account has been found to support or refute it. That’s the problem with history. It’s a bit like Schrödinger’s cat. Sometimes you think you’ve got it and then you find out you haven’t!

Are you still curious? Is that cat still breathing? Why don’t you do your own digging and try to prove me wrong?

And while you’re doing so, don’t forget these five key questions:

- How reliable is this account? Was it written by an eye-witness? Was it written at the time? Did the author really understand what they were writing about?

- Why was it written? Was it just to make money or to curry favour? Was it meant to persuade people of something?

- Who was it written for? Was it for public consumption? Was it intended to be read at all?

- What was the context? How does it fit in with what was happening at the time? Do the words still mean the same thing?

- Can you find anything that backs it up? Do other primary sources support your interpretation?

All very curious…

Notes

*Transcribed in Witch Hunting and Witch Trials: The Indictments for Witchcraft from the Records of the 1373 Assizes Held for the Home Circuit AD 1559-1736 (1929) edited by C. L’Estrange Ewen, p.197