When two heads are better than one

For a writer, there’s nothing scarier than a blank piece of paper or screen. It accuses you with its glare, ‘Think you can beat me, do you? Who are you kidding?’

That first scribble or tentative tap of the keys can be the most difficult. What if there’s nothing to say? Or, if there is, what if I just can’t say it?

Sometimes you just have to face your fear down. Sometimes you just have to write.

Get over it – it’s not life or death! What you write may not be any good – it almost certainly won’t correspond to the beautifully-crafted phrases in your head. Quite frankly, it will probably be rubbish. But as someone else said, you can always edit a bad page – you can’t edit a blank one.

I start with a scrap of information, a gut feeling, much research and a few scribbled phrases. And lots and lots of walking. Mind-time: it’s one of the two things you can’t do without. (The other is a space to sit and write in.) The process is a messy one and can be infuriating. This is how one of the poems behind Cracked Voices nearly ended up in the bin, only to saved by some well-timed criticism…

A scrap of information

A scrap of information

In the Sedgwick Museum in Cambridge there’s the skeleton of a hippopotamus that was dug up at Barrington. (I know this because we chanced upon it there when my kids were small. I’d taken them into the museum to see the dinosaurs.) It was discovered during the Coprolite mining rush that swept across south Cambridgeshire in the 1860s and 70s. Both the hippo and the diggers are now largely forgotten.

A gut feeling

Apart from the obvious, there must be something deeper that linked this hippo to the fate of the men who mined the ground. These people needed their story digging up!

Much research

A search on Google threw up the works of Bernard O’Connor who has written extensively on the coprolite quarries (along the way rediscovering the words of a folksong written at the pits in the 1870s by one of the diggers), Royston Museum came up with a copy of Richard Grove’s book from 1976 and a search through the British Newspaper Archive came up with name upon name of men who had been killed digging out the fossils. It was shocking to read how so many men were crushed to death, quite literally buried alive. Further research in the censuses showed that it was not unknown – probably out of economic necessity – for the widow of a digger to marry one of his workmates. Louisa Seabourne at Bassingbourn thus became Louisa Sell and then Louisa Starr.

It was about this time that the Sedgwick Museum came back to me with some serendipitous news. The hippo was not a hippo at all. Bones from several hippos had been stuck together. This was a composite animal.

A few scribbled phrases

the ground demands its fill / a man of many parts / like the bones of the hippo they found in the pit, it’s a puzzle to know where each scrap of you fits

Mind-time

On a walk it came to me that this should be a two voice poem. One voice should be that of a dead coprolite digger (based around the skeleton of the folk-song) and the other that of his wife or lover. The fossiler would sing for all the dead diggers and give them a composite voice.

Drafting

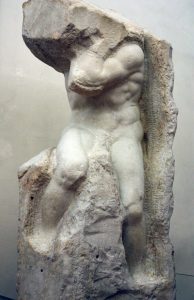

Some of the works of art that I love most have never been finished. There is something in their incompleteness that is deeply satisfying. When I was Inter-railing I chanced upon Michelangelo’s unfinished slaves in the Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze. They are breath-taking as they struggle to free themselves from the blocks of marble. Drafting is just like that. You take an idea – a plan often only sketched out in your head – and then you start tapping away at it, incorporating the imperfections into something that may end up far better or, in most cases, far worse than what you originally had in your head. But gradually something emerges…

Image courtesy of Accademia.org

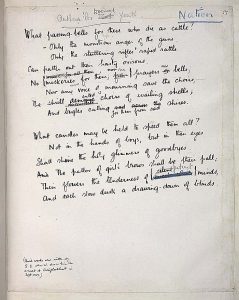

The novelist Tim Winton (two-times Booker Prize nominee and four times winner of the Miles Franklin Award) refuses to type, claiming typed drafts look too much like the finished thing and fool you into thinking you’re done when you’re not. Instead he writes the old fashioned way in order to slow himself down enough for the idealised words in his head to translate into real words on the page, not with a pen but with a pencil. The marks a pencil makes are more tentative, easier to cross out or erase. I do both interchangeably…tending towards the computer as the final few drafts emerge…and one of the things I have learned, is not to be too precious. Just look at the drafts of Wilfred Owen’s poems, with Siegfried Sassoon’s scribbled alterations. Sometimes the writer is too close to the original. Sometimes two heads are better than one.

My initial plan for this poem was to echo the form of the original folk-song (which has a young man thumbing his nose at his previous employer) but also make it a conversation between two people who aren’t really listening to each other…a sort of delayed call and response. Once I had it nearly finished, I shared a draft with my nearest and dearest as I had niggling doubts – it was not quite there. My son was to the point, ‘The first bit feels a bit like a middle class parody of a folk song!’ He was right. Despite being only slightly altered from the original nineteenth century song, it didn’t feel authentic. I went back and rewrote it (still not right) and then sent it winging through the ether to Jenni. ‘I know it’s a duet,’ she replied. ‘One thought that immediately popped into my head was to make the male and female parts work together, so the last two stanzas could be repeated together – what do you think?’ I looked again. Whether she knew it or not she had hit the nail squarely on the head. It was not just the last two stanzas that needed to work together…it was the complete thing. By cutting up the two monologues and pasting them together it became a dialogue with some unusual linking. Instead of a parody it had become a modern composite and somehow, along the way, the blank paper had spawned a poem. Job done.