The migraine and the goddess

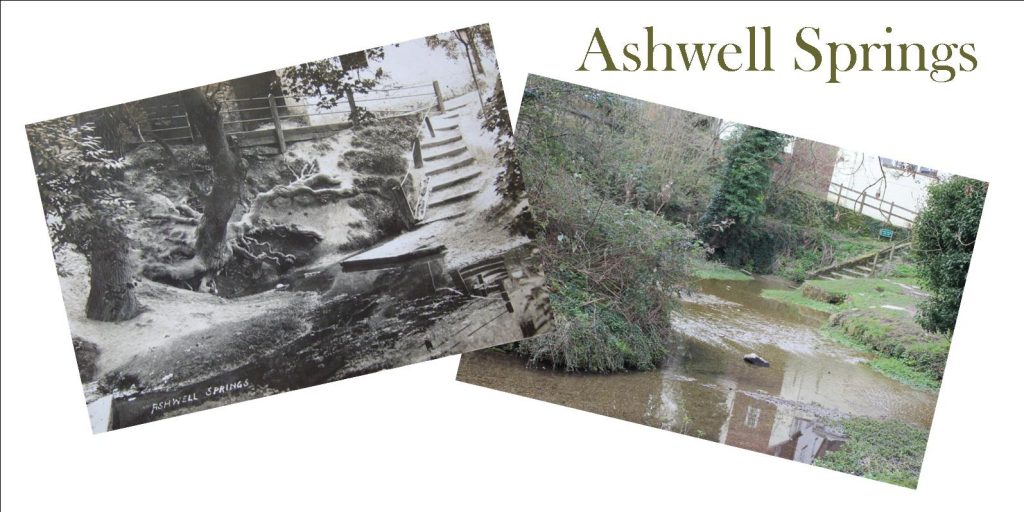

At Ashwell in Hertfordshire some not-so-ancient concreted steps lead down to the village’s liquid heart. Here the springs bubble up onto gravel or trickle through cracks, draining off the chalk escarpment to the south. Apart from the steps, the scene has not much changed since Nathaniel Salmon described it in the History of Hertfordshire back in 1728:

“… the River Rhee…breaks out of a Rock in this Vill from many Springs, with such Force as to form a Stream, remarkable for being clear, and so cold, that it gripes Horses not used to drink it. Around the Spring Head grow Ash Trees very kindly, which gave occasion to the Name.”

Officially, Ashwell Springs is now a Site of Special Scientific Interest but it has always been of interest to those of a more mystical nature. Coupled with the ash (a sacred tree that linked the waters of the lower world with our own world and the sky above), the springhead has fascinated us for millennia.

It was not so long ago that such springs and ponds were considered sacred and were even, on occasions, known to yield treasure (old votive offerings from long dead people to the water-giving spirit or god). Perhaps this is why the shallow dew pond (now vanished) which watered animals at the foot of nearby Therfield Heath was once known as the Golden Bog. No treasure survives there now, just a patch of dry nettles thriving on soil enriched with the manure and sediment from the pond’s bottom.

It was not so long ago that such springs and ponds were considered sacred and were even, on occasions, known to yield treasure (old votive offerings from long dead people to the water-giving spirit or god). Perhaps this is why the shallow dew pond (now vanished) which watered animals at the foot of nearby Therfield Heath was once known as the Golden Bog. No treasure survives there now, just a patch of dry nettles thriving on soil enriched with the manure and sediment from the pond’s bottom.

But mysteries are still unearthed. In 2002, some distance northwest of Ashwell’s wellhead near the bank of the Rhee, a metal-detectorist called Alan Meek was sweeping a field at Ashwell End when he came across an extraordinary cache of metal objects that had been hidden in the ground over sixteen hundred years ago. It proved a spectacular rebirth as nearly thirty offerings to a previously-forgotten Celtic goddess appeared from the soil. Many were marked with the name Senuna and there was also a shattered silver figurine of the goddess herself.

There are various mother goddesses known to be associated with springs but little survives of Celtic Senuna. Many of the offerings from Ashwell End show her accompanied by an owl and armed with a spear and shield, suggesting that when the Romans invaded Britain they may have assimilated her into the cult of Minerva. At that time, as Julius Caesar noted in Commentarii de Bello Gallico, the worship of Minerva (or her native equivalents) was prevalent in the Celtic continental heartland of Gaul. Minerva was the Roman goddess of water, healing, warfare, crafts and wisdom and was usually depicted with a sacred owl, a symbol of wisdom but also a harbinger of death.

This Roman goddess had a penchant for creative destruction which stemmed back to her strange birth. She had been born from the union of Jupiter (the sky-father who carried a thunderbolt) and a female titan. When the titaness fell pregnant the prospective father was not overjoyed because it had been prophesied that his own child would eventually overthrow him. His solution was to swallow his lover whole before she could give birth. Trapped inside Jupiter, the titaness set about forging weapons and armour for her soon-to-be-born daughter. The stress and the racket of his ex-lover’s new hobby gave Jupiter such a migraine that he persuaded Vulcan to split his head open with a hammer and, lo-and-behold, out of the cleft jumped Minerva, fully-grown and armed to the teeth. But Minerva was destined to become a goddess of wisdom as well as war, so she made things up with her father…but that’s another story.

This Roman goddess had a penchant for creative destruction which stemmed back to her strange birth. She had been born from the union of Jupiter (the sky-father who carried a thunderbolt) and a female titan. When the titaness fell pregnant the prospective father was not overjoyed because it had been prophesied that his own child would eventually overthrow him. His solution was to swallow his lover whole before she could give birth. Trapped inside Jupiter, the titaness set about forging weapons and armour for her soon-to-be-born daughter. The stress and the racket of his ex-lover’s new hobby gave Jupiter such a migraine that he persuaded Vulcan to split his head open with a hammer and, lo-and-behold, out of the cleft jumped Minerva, fully-grown and armed to the teeth. But Minerva was destined to become a goddess of wisdom as well as war, so she made things up with her father…but that’s another story.

There are displays on Senuna at both at the British Museum (Room 49) and at Ashwell Village Museum. Given the similarities in names, it has been argued that the lost British river Senua mentioned in the Ravenna Cosmography (a geographical work written by an anonymous cleric in Ravenna in Italy around AD 700) may well be the Rhee. Certainly, Ashwell was known much further afield than it is now. One of the offerings of jewellery to Senuna found in 2002 bears the simple inscription,

“Servandus, son of the Spaniard, willingly fulfilled his vow to the goddess.”

So much is buried, hidden deep from us. Who was this Spaniard’s son whose name means to watch over, preserve or save? What was he doing in rural Hertfordshire? What was his vow and why had he made it? History is full of such uncertainty. Trying to break through to some sort of understanding can cause us all sorts of headaches. Just ask Senuna-Minerva.

‘Those who wait’, the first song in Cracked Voices, will revolve around the relationship between Sevandus and Senuna.